From Nature today is the article Environment: Waste production must peak this century

|

| When Will Waste Peak? |

Peak waste

The rate at which solid-waste generation will rise depends on expected urban population and living standards growth and human responses. In 2012, two of us (D.H. and P.B.-T.) authored a World Bank report, What a Waste1, which estimated that global solid-waste generation would rise from more than 3.5 million tonnes per day in 2010 to more than 6 million tonnes per day in 2025. These values are relatively robust, because urban populations and per capita GDP can be well forecast for several decades.

Nature special:Science and the city

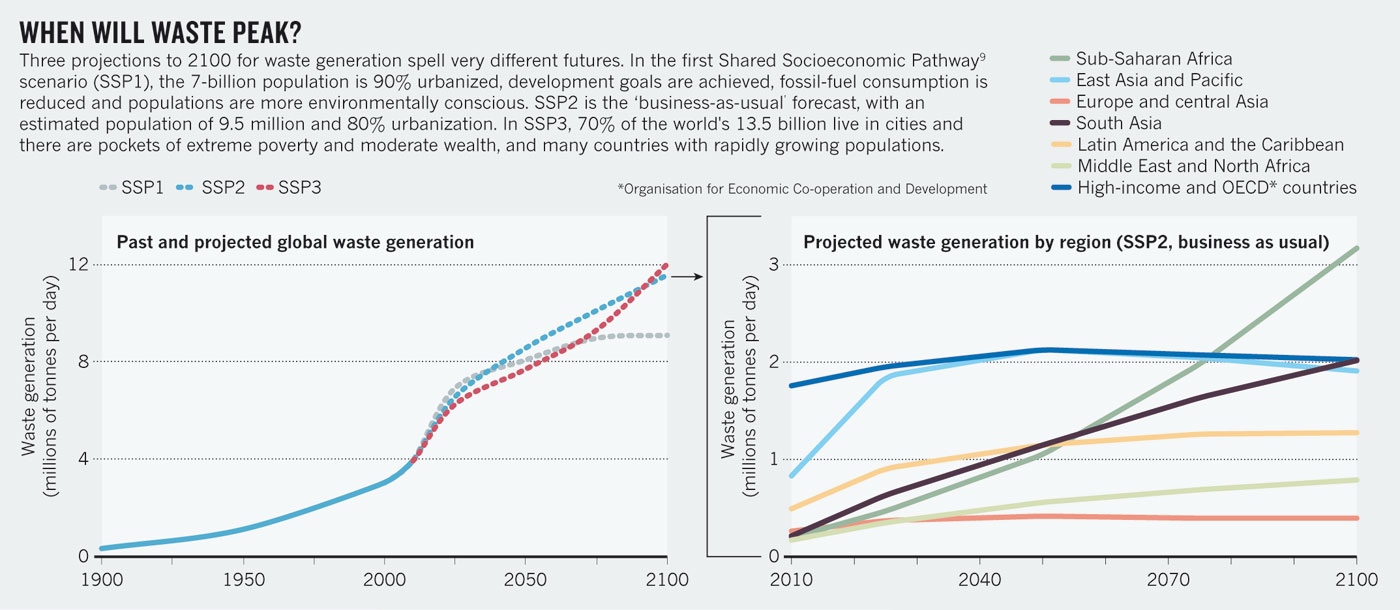

Extending those projections to 2100 for a range of published population and GDP scenarios shows that global 'peak waste' will not happen this century if current trends continue (see 'When will waste peak?'). Although OECD countries will peak by 2050 and Asia–Pacific countries by 2075, waste will continue to rise in the fast-growing cities of sub-Saharan Africa. The urbanization trajectory of Africa will be the main determinant of the date and intensity of global peak waste2.

Using 'business-as-usual' projections, we predict that, by 2100, solid-waste generation rates will exceed 11 million tonnes per day — more than three times today's rate. With lower populations, denser, more resource-efficient cities and less consumption (along with higher affluence), the peak could come forward to 2075 and reduce in intensity by more than 25%. This would save around 2.6 million tonnes per day.

Convert and divert

How can today's situation be improved? Much can be done locally to reduce waste. Some countries and cities are leading the way. San Francisco in California has a goal of 'zero waste' (100% waste diversion by reduction and recycling) by 2020; already more than 55% of its waste is recycled or reused. The Japanese city of Kawasaki has improved its industrial processes to divert 565,000 tonnes of potential waste per year — more than all the municipal waste the city now handles. The exchange and reuse of materials connects steel, cement, chemical and paper firms into an industrial ecosystem3.

“Waste will continue to rise in the fast-growing cities of sub-Saharan Africa.”

North America and Europe have tried disposal fees, and found that as fees increase, waste generation decreases. Another tactic is to steer people to buy less with their increased wealth, and to spend more on experiential activities that require fewer resources4, 5.

But greater attention to consumption and improvement in waste management is needed in rapidly urbanizing regions in developing countries, especially in Africa. Through increased education, equality and targeted economic development, as in the sustainability scenario we evaluated6(SSP1), the global population could stabilize below 8 billion by 2075, and urban populations shortly thereafter. Such a path reflects a move towards a society with greater urban density and less overall material consumption7. Also needed is a widespread application of 'industrial ecology' — designing industrial and urban systems to conserve materials. This begins with studies8 of the urban metabolism — material and energy flows in cities.

Reducing food and horticultural waste is important — these waste components are expected to remain large. Construction and demolition also contribute a large fraction by mass to the waste stream; therefore, building strategies that maximize the use of existing materials in new construction would yield significant results.

The planet is already straining from the impacts of today's waste, and we are on a path to more than triple quantities. Through a move towards stable or declining populations, denser and better-managed cities consuming fewer resources, and greater equity and use of technology, we can bring peak waste forward and down. The environmental, economic and social benefits would be enormous.

- Nature

- 502,

- 615–617

- ()

- doi:10.1038/502615a

- Read the whole article here

- References:

- Hoornweg, Daniel, Perinaz Bhada-Tata, and Chris Kennedy. Nature, "Environment: Waste production must peak this century." Last modified October 30, 2013. Accessed October 30, 2013. http://www.nature.com/news/environment-waste-production-must-peak-this-century-1.14032.

No comments:

Post a Comment