Since the end of The Great Recession the focus has been on the moribund job growth in the United States and the hara kiri policy bloodletting in the Eurozone that will ensure at least a lost decade and probably more for the population in the euro periphery. This has provided shelter for Canadian policymakers with the National Post going so far as to say that "At G20, Flaherty still has his economic bragging rights."

But the game of bragging (when there is nothing to truly brag about) is afoot and for those clinging to the questionable certainty of mean reversion the coming year will be a testing one. Will new Bank of Canada Governor, Stephen Poloz, and the governing council raise rates by this time next year? This blog has gone on record in maintaining the view that barring Promethean internationally co-ordinated policy (which is highly unlikely) Canadians are in for a secular period of low rates with none of the expected rate normalization seen in previous cycles.

Amongst the many reasons for rate hike scepticism, the composition of job growth is most troubling with 4 of 5 new employees finding temporary employment since the recession began in 2008..

|

| Canada: Growth in permanent and temporary workers |

Globe and Mail economics reporter Tavia Grant explored this further in her recent piece, "Canada's shift to a nation of temporary workers":

What many employers would call flexible work, others would call precarious. A joint study by McMaster University and the United Way in February found four in 10 people in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton region are in some degree of precarious work (defined as a state of employment that lacks security or benefits) – and that this type of employment has risen by nearly 50 per cent in the past two decades. It also found that people in insecure work tend to earn 46-per-cent less than those in secure positions, and rarely get benefits.

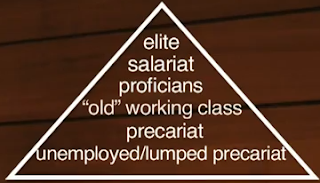

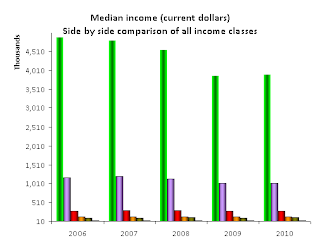

Fitting Standing's class structure into a stylized income segmentation of tax filers in Toronto, one comes to a troubling observation: how do people on such relatively low incomes get by in an increasingly expensive city? Toronto is simply another example of what has happened elsewhere: cities gentrifying and becoming increasingly expensive for a greater portion of the population.

Precariat et al.

|

| All tax filers in Toronto (median income 2010) = $27,200 |

Middle Class

|

| Top 10% Toronto (median income 2010) = $104,600 |

Upper Middle Class

|

| Top 5% Toronto (median income 2010) = $135,700 |

Proficians

|

| Top 1% Toronto (median income 2010) = $283,400 |

|

| Top 0.1% Toronto (median income 2010) = $1,024,200 |

Elite

|

| Top 0.01% Toronto (median income 2010) = $3,898,800 |

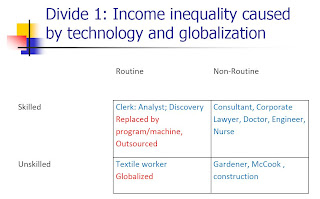

With the majority of job growth coming in the form of temporary jobs it begs the question of what will be the future catalyst for growth? The increasingly precarious nature of employment today begets more "losers" and fewer "winners" tomorrow. The marginal propensity to consume for those consigned to temporary work will be higher and conversely the marginal propensity to save lower as will the ability to save up for a down payment. In turn, how will this segment be able do the things that Canadians in generations past took for granted, such as buying a single family residence, due to the barrier to entry of high house prices. Moreover, the rising inequality we see today will manifest itself with pensioners tomorrow that are knee deep in debt and working to make ends meet. This is part of the irresistible forces of the globalization model and technology that has enabled the disappearance of many jobs.

And it will continue. William H. Janeway remains someone who understands the capitalist system for what it is --inherently unstable yet dynamic and full of opportunity-- had this to say recently:

The processes of creative destruction continue to play out. Five years ago Nokia and Motorola ruled the mobile world, with Blackberry as the leader in the enterprise market. Where are they now? Plus the maturation of open source technologies and access to cloud-based computing and storage resources on an as needed basis has radically reduced the cost of development for new start-ups. Even Apple's extraordinary success is beginning to look transient in the post-Jobs age.

How does one contend with such change when planning for the future? There are no easy answers but the steady dismantling of the social contract embedded since the time of Lester B. Pearson will create ferment, resentment and anger amongst those left behind in a society of fewer "winners" and many more "losers".

No comments:

Post a Comment